21 August 2018

This has been is a week of firsts. Tuesday morning, I wrote an email to my oldest daughter (she was too young to exchange email with before) saying: ‘I’m going in the ALVIN today to visit the animals at the bottom of the ocean. I’m excited”. Little did I know how perfectly those words – visiting animals at the bottom of the ocean – would fit the dive.

It is exceedingly rare to have the opportunity to do something that no human being has ever done before. For me, Tuesday was one of those days: I was one of three scientists in the research submersible ALVIN traveling to a depth of some 500m along the continental slope off the southeast US coast to visit a recently discovered seep field, the Pea Island Seeps. This site was mapped using an AUV but before our dive, it had never had “eyes on the bottom”, via either a remotely operated vehicle or a human occupied vehicle. Tuesday, we visited the area with the ALVIN and oh what a dive it was.

The Pea Island area is characterized by widespread gas seepage. We know this because we mapped the area using the multibeam echo sounder (MBES) and observed diffuse areas of gas seepage as well as gas flares. Some of these flares were strong enough to generate vertical plumes that reached 300m above bottom. Such strong flares link seabed and water column processes, at times, even connecting the seafloor with the surface ocean.

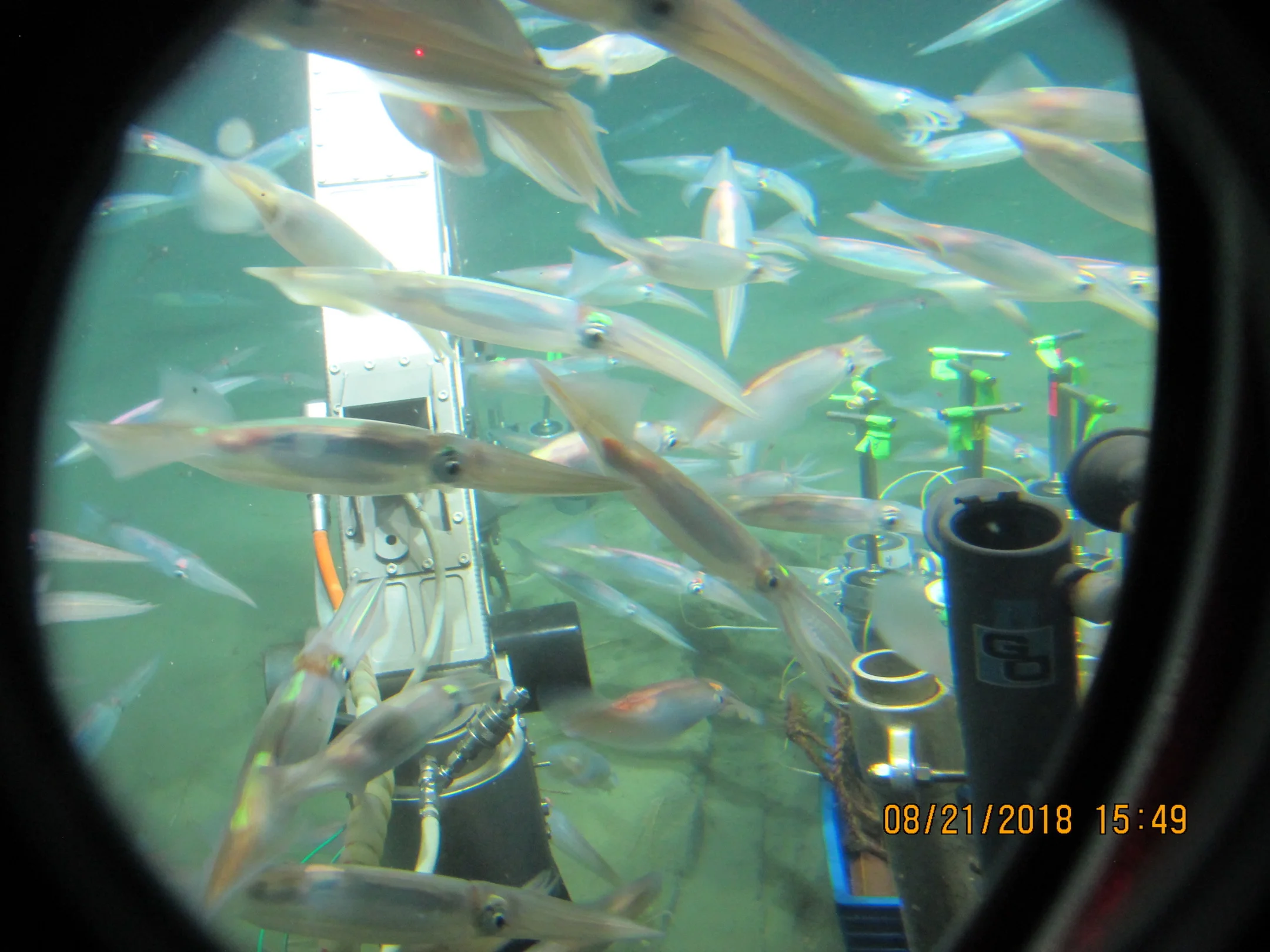

The dive was packed with unexpected events. We landed close to the target – waypoint 1 – and observed soft, brown sediment inhabited by a diverse suite of animals: anemones, worms, shrimps, crabs, small and large fish, eels, squid, and more. There were many, many squid and they were curious and intrusive times. The squid managed to interfere with everything from visibility, by obscuring the windows, to coring, by dancing around the manipulator as we attempted to core and disturbing the sediment by blowing away patches – literally – in the mats as we tried to sample them.

Our goals on this dive were to characterize the area and to collect sediment samples from areas of seepage, microbial mats dominated by Beggiatoa, and from any areas that lacked seepage, the latter serving as comparative controls. Fairly quickly, we found areas covered by thick Beggiatoa mats and we saw methane bubbles emanating from various small vents all across the mat area. Beggiatoa are gammaproteobacteria that can oxidize hydrogen sulfide to sulfate using either oxygen or nitrate as the electron acceptor. These “giant” filamentous bacteria are visible to the naked eye. They form thick markers, acting as a bulls-eye at the seabed marking areas of active seepage. We sat ALVIN down and commenced coring. After collecting nine sediment cores from the Beggiatoa mat, we flew over it to obtain video describing the site.

We then embarked on a run to try and locate the large gas vent that we observed with the MBES. Unfortunately, we did not find the vent but we saw a number of interesting features. We observed carbonate outcrops – probably authigenic (which means ‘formed in situ’) carbonates. The carbonates were home to a lot of sessile (anemones, …) and mobile animals. We collected carbonate rocks for characterization back in the lab and for use in microbiology experiments.

From there, we moved on towards a northern line. About ½ way there, we stopped and sampled non-seep sediment. These sediments were brown and occupied by worms. Other animals (squid were still with us) were also present. We sat down and collected samples and then moved further north. Along the second line, we found more microbial mats and sampled them.

When we finished sampling, about 8 hours after boarding ALVIN, we signaled that we had completed our mission and were ready to return to the surface.

I’ve been lucky enough in my career to do a lot of submersible dives and roughly 1/3 of my dives have been in the ALVIN. There is something surreal about diving to the bottom of the ocean in this amazing and famous vehicle. The first few minutes on the bottom are amazing – just taking it all in and appreciating the beauty and diversity of the deep sea. It never gets old and each dive is a new, incredible experience. Every dive, I see something I have not seen before. Every dive teaches me something I did not know about the deep sea. And, every dive leaves me with a number of questions I need – and want – to answer, serving as fodder for new experiments and possibly, new projects.

For more about our expedition, please see NOAA’s Ocean Explorer web site, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/18deepsearch/welcome.html, or follow us on Twitter @OceanDeepSearch, @DeepseaECOGIG, @BOEM_DOI, @oceanexplorer, @thenopp, @USGS, @CordesLab, @ademopoulos, @SeepExplorer, @c_m_dangelo or by searching for the hashtag #DeepSearch.