AT 42-05 | 18 November 2018

Hot stuff

Hydrothermal environments are dynamic; things change often and they change fast. Understanding how microbial populations and activity are shaped by thermal and chemical gradients is one of our primary research objectives here in Guaymas Basin. These extreme habitats are an ideal place to search for new microorganisms and new metabolisms and to probe the temperature limits of life. Opportunities for discovery abound.

Alvin Dive 4991 was UGA PhD student Andy Montgomery’s first dive.

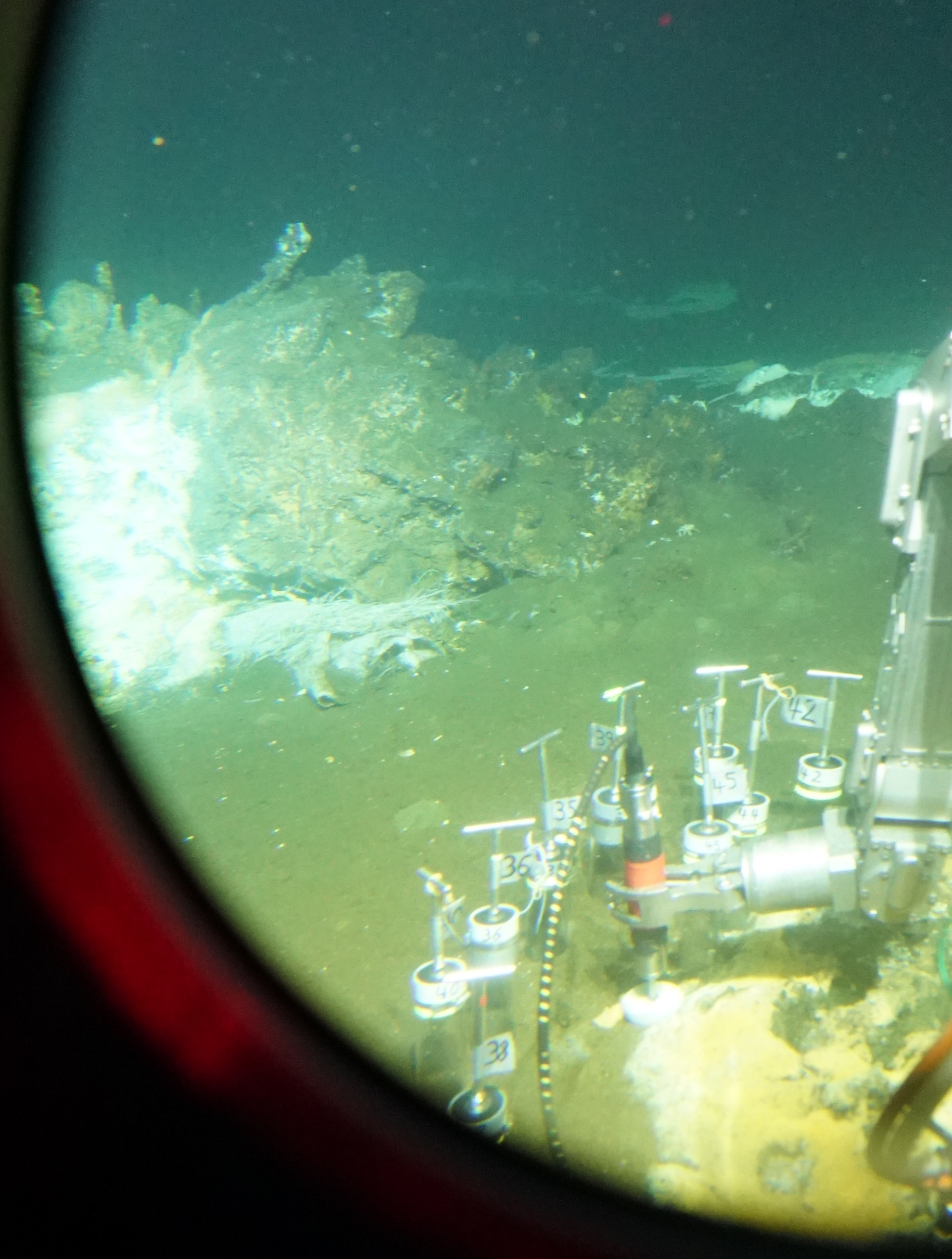

We visited Cathedral Hill, a site that has been sampled before and one we know well. We landed a bit to the NE of the previous sampling area and found ourselves surrounded by beautiful small (1.5m) hydrothermal spires and even more small vents along the seafloor. Colorful Beggiatoa microbial mats carpeted the seabed around areas of hydrothermal seepage.

This environment may seem simply beautiful, but it is extreme and challenging for the organisms that live here. We inserted a heat flow probe into the seabed using the ALVIN’s Schilling manipulator.

Beneath the orange Beggiatoa mat, temperatures reached 67ºC at 25cm and were 99ºC at 50 cm beneath the mat (see the dark blue line and sensor T9 data on the temperature log figure). Life thrives along these extreme thermal gradients.

Hydrothermal fluids moving through the sediments generate steep thermal gradients. These fluids are also enriched in reduced chemicals that provide metabolic fuel – for example, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and ammonium – for the microbial communities that live there. The colorful Beggiatoa mats oxidize hydrogen sulfide to sulfate and this sulfate provides metabolic fuel by other microorganisms that live in association with the Beggiatoa. Numerous feedbacks between elemental cycles exist, creating puzzles involving energy flows and metabolic exchanges for the science team to ponder and resolve.

Despite the harsh conditions along the seabed in Guaymas Basin we often see fish, eels and even octopus. We spotted a shy octopus watching us from a distance during this dive.

Some animals – squid! – are attracted to the lights and curious and they often come up to the submarine to check it out. Others pretend to be invisible and sit still, hoping not to be noticed. This octopus fell into the latter category.

During the last part of our dive, something strange, something that was out of place. At the base of a chimney, a large white object caught my eye. It took me a moment to realize what it was … a large plastic seed bag. Yes, we found plastic trash at the bottom of the ocean in a beautiful hydrothermal vent field. This painful reminder underscores the reach of plastic pollution, which reaches the depths of the ocean basins and spoils sites like this. We need to be better stewards of the ocean and we all need to dial back our use of plastics.